Washington state Supreme Court OKs steelhead farming for Cooke Aquaculture

Permits that will allow Cooke Aquaculture Pacific to farm steelhead trout in net pens in Washington waters were upheld in a unanimous 9-0 decision by the state Supreme Court Thursday.

The decision clears the permit hurdle for the international aquaculture giant to change up its operations in Washington from farming Atlantic salmon to steelhead.

That’s good news for Cooke — and the Jamestown S’Klallam tribe, which in 2019, announced a joint venture with Cooke Aquaculture Pacific to rear native steelhead trout.

“The Tribe has two interwoven goals in everything we do — to be stewards of the environment in protecting the unique ecosystems of our homelands and the Salish Sea and continue to gather our treaty resources to fund programs and services for our tribal citizens,” said W. Ron Allen, chairman of the tribe in a prepared statement. “Aquaculture allows us to utilize best practices in protecting the environment while continuing our traditional industries growing and gathering marine-based resources.”

Joel Richardson, vice president of public relations for Cooke, said the Supreme Court opinion “lays to rest the array of disinformation about marine aquaculture being irresponsibly circulated by activist groups.”

The Washington state Legislature in 2018 phased out Atlantic salmon farming in Washington waters following a spill of about 263,000 nearly mature Atlantics from Cooke’s pens at Cypress Island in August of 2017.

So Cooke is pivoting to farm steelhead, a native species, with fish that are altered in a Washington state based fish farm to be sterile.

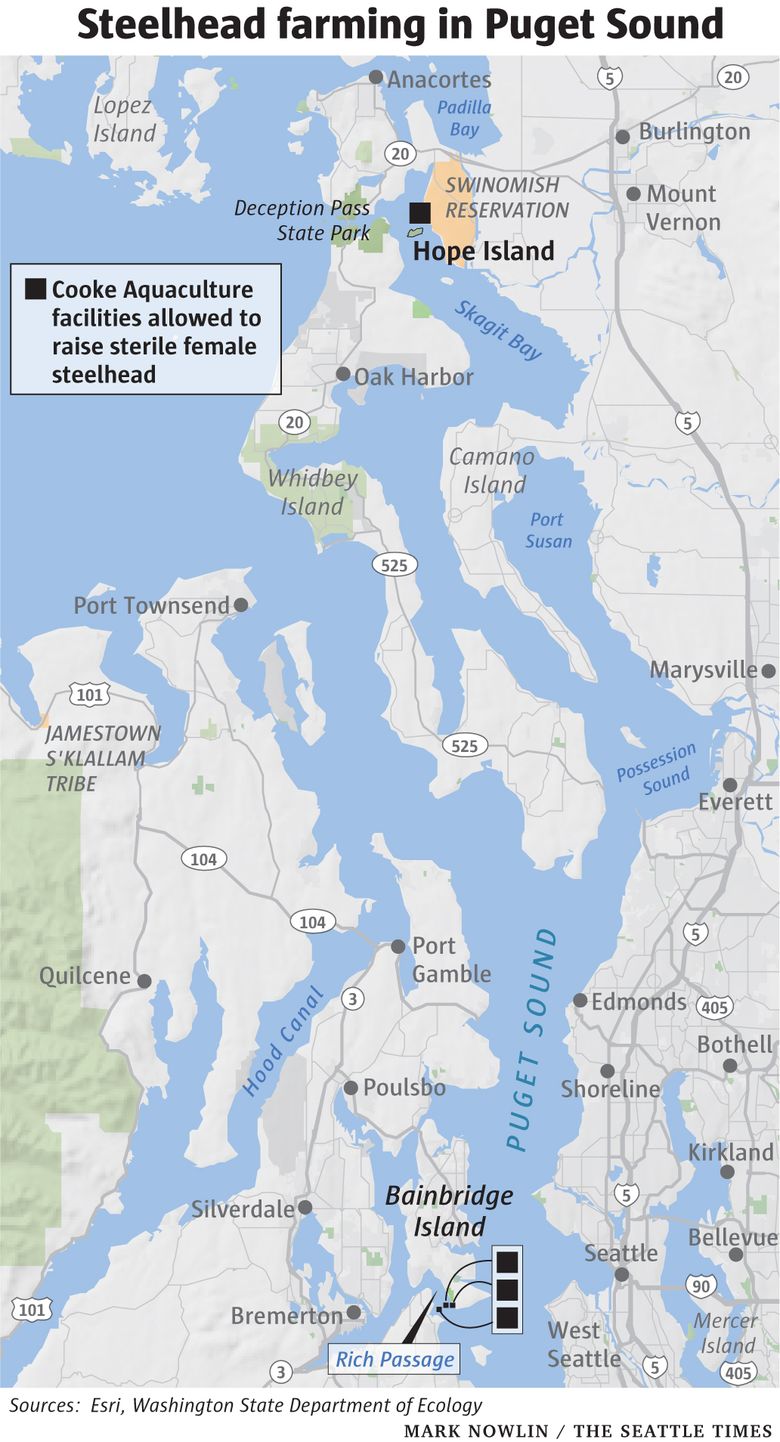

The court’s decision affirms the five-year marine finfish aquaculture permit the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) issued to Cooke in January 2020. Cooke is already rearing all female, sterile steelhead trout at two locations, its Hope Island net pen near the mouth of the Skagit River and its Clam Bay net pen in Rich Passage.

The WDFW issued permits to move fish into the net pens in August 2021 at Hope Island and Clam Bay in October 2021. Both sites are now fully stocked.

Opponents argued in King County Superior Court that the WDFW had not adequately reviewed the permit under state administrative procedures or required adequate environmental review. The opponents, who lost the case, wanted the court to overturn the permits and require an environmental-impact statement.

The state and Cooke argued the review fulfilled all legal requirements — and two courts have now agreed.

The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community had joined the opponents as a friend of the court, arguing the net pen at Hope Island interferes with exercise of tribal fishing rights, and is an insult to the integrity of a place with immense cultural importance.

The tribe also argued the fish pose a risk to native steelhead.

Kelly Susewind, director of WDFW, said in an prepared statement he was pleased with the decision.

“The Court conducted an extensive review of the arguments against WDFW’s permit decision and environmental analysis, and it unanimously held that WDFW’s review was ‘more than sufficient.’ This stands as a strong endorsement of WDFW’s handling of the permit,” Susewind said.

While the net pens “are not a zero-risk” operation, “we required Cooke Aquaculture to adhere to 29 mitigating provisions to guide operation of its facilities, to prevent and report potential disease, and to reduce the risk of fish escaping and improve reporting in the event of escape.”

While the Supreme Court has spoken, the battle over net pens is just beginning, said Kurt Beardslee, director of Wild Fish Conservancy, who called the decision “devastating.”

The real fight will gear up this year when the state Department of Natural Resources begins determining whether to renew state leases for the tidelands over which the pens are placed. That will be a more wide-ranging review, Beardslee said, that considers everything from tribal treaty rights to endangered-species concerns.

The DNR has already put Cooke on notice that it may want to think twice before stocking its pens.

Chairman Steve Edwards of the Swinomish tribe signaled the tribe’s continued disagreement with the net pen that has been operating in their treaty fishing grounds for decades. “We respect the court’s ruling and remain hopeful that the Hope Island net pen, which presents ongoing interference with the Swinomish Tribe’s treaty fishing access and is antithetical to the Tribe’s lifeways and culture, can be removed in the coming months.”

The Northwest Aquaculture Alliance, a trade group, celebrated the decision.

Jim Parsons, president of the alliance and former general manager of Cooke Aquaculture, said the Supreme Court opinion is a boost to aquaculture not only in Washington, but elsewhere. “As an industry,” Parsons said in a prepared statement, “we are heartened to see a decision that essentially normalizes fish farming in Washington.”